— This blog post was written by Dr Julie Van Pelt, postdoctoral fellow of the FWO.

One of the main advantages of going abroad for research is the opportunity to travel and experience different cultures. A few weeks ago, during my appointment as a visiting scholar at Georgetown University in the US, I attended a Fulbright event hosted by the Flanders House in New York (see photo). I decided that I had to take advantage of the city’s recent post-pandemic reopening to attend a show at the legendary heart of the entertainment business. Excitement, bold colours, flashing lights, bustling crowds: Broadway! The actual show I found not that exciting, but that is beside the point: I could now proudly say that I had witnessed a paragon of American culture, and call it a day. While the idea of seeing a Broadway show had been raised as a self-evident New York activity, my interest in going was fuelled by memories of a specific movie: Birdman or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance) (directed by Alejandro González Iñárritu, 2014).

One of the main advantages of going abroad for research is the opportunity to travel and experience different cultures. A few weeks ago, during my appointment as a visiting scholar at Georgetown University in the US, I attended a Fulbright event hosted by the Flanders House in New York (see photo). I decided that I had to take advantage of the city’s recent post-pandemic reopening to attend a show at the legendary heart of the entertainment business. Excitement, bold colours, flashing lights, bustling crowds: Broadway! The actual show I found not that exciting, but that is beside the point: I could now proudly say that I had witnessed a paragon of American culture, and call it a day. While the idea of seeing a Broadway show had been raised as a self-evident New York activity, my interest in going was fuelled by memories of a specific movie: Birdman or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance) (directed by Alejandro González Iñárritu, 2014).

The movie is, in fact, about a play. The near-forgotten Hollywood actor Riggan Thomson, whose career took flight with his role as the superhero Birdman in the eponymous blockbuster but now threatens to crash prematurely, is preparing a Broadway production in the hope of saving his reputation as a respected artist. What has always fascinated me about Birdman is that it deliberately blurs the distinction between reality and illusion. The medium of live performance particularly challenges this distinction. The movie offers a forceful reflection thereon, yet, as I came to learn during my doctoral research, it is something that was already felt by the Byzantines.

Super-Realism

Birdman’s main vehicle for thematising the faded boundaries between reality and illusion is the protagonist himself. In the movie, it becomes evident that Riggan is struggling with some issues, which at times hinder his professional endeavour. The problem is that he identifies himself with his character, Birdman. He is plagued by delusions in which he, Riggan, Birdman, has supernatural abilities. Or are these not delusions at all, which exist only in his head, and is he truly an extraordinary person, yet no one can see his true value? Both options are deliberately presented as equally possible. There are various other ways in which the same blurriness regarding what is real and what is illusion comes to the fore in this movie, specifically in the context of the play that is being rehearsed. One of the actors featuring in it, Mike Shiner, owes his success on the stage to his strategy to keep it real while acting but turns out to be a shallow pretender in real life. For instance, he resorts to what may be called method acting and drinks on stage. Unable to engage in sincere connections with his co-actors off-stage, however, he is accused by one of them of being a ‘fraud’ in spite of his professional reputation as ‘Mr Truth’.

Birdman’s main vehicle for thematising the faded boundaries between reality and illusion is the protagonist himself. In the movie, it becomes evident that Riggan is struggling with some issues, which at times hinder his professional endeavour. The problem is that he identifies himself with his character, Birdman. He is plagued by delusions in which he, Riggan, Birdman, has supernatural abilities. Or are these not delusions at all, which exist only in his head, and is he truly an extraordinary person, yet no one can see his true value? Both options are deliberately presented as equally possible. There are various other ways in which the same blurriness regarding what is real and what is illusion comes to the fore in this movie, specifically in the context of the play that is being rehearsed. One of the actors featuring in it, Mike Shiner, owes his success on the stage to his strategy to keep it real while acting but turns out to be a shallow pretender in real life. For instance, he resorts to what may be called method acting and drinks on stage. Unable to engage in sincere connections with his co-actors off-stage, however, he is accused by one of them of being a ‘fraud’ in spite of his professional reputation as ‘Mr Truth’.

In Riggan’s case, reality and illusion are intertwined to such a degree that it is impossible to tell them apart. Mike, on the other hand, deliberately uses that ambiguity as a coping mechanism to be successful both on and off the stage, but, switching out reality for illusion, he loses his way too. Another character, one of the actresses in the play, has to deliver a monologue about pregnancy which becomes strangely meaningful to her ‘real’ self when she finds out that she is actually pregnant. The movie pushes the disorientation game even further: when, in one scene, Mike and Riggan walk down the street, their conversation is underscored with a jazzy tune, which at first appears to be a non-diegetic feature of the movie as filmic composition, but, when a street performer enters the shot, turns out to be a diegetic element ‘truly’ belonging to the story world. When the play finally premiers, Riggan shoots himself on stage with what was supposed to be a harmless weapon in the play’s dramatic closing scene. Rather than being abhorred by the spectacle, the long-feared and vicious New York Times critic praises it euphorically and calls it a new form of ‘super-realism’. The movie thus views the medium of live performance through a critical lens by thematising the ways in which it challenges the distinction of reality and illusion. It so happens that, perhaps without realizing it, the filmmaker has hereby reinvigorated some very old debates about the nature of performance.

Christian Theatre: an Oxymoron?

Byzantium, though it is essentially the direct political and cultural continuation of Greco-Roman society which gave birth to the theatre, never developed a form of theatre of its own. Pagan theatre nevertheless continued to exist well into the Christian era, at least until the 6th century, and was especially popular in cities such as Antioch. However, the Church fathers tried very hard to dissuade the public from attending those spectacles. Among the reasons they disliked it were its ties to the pagan ritual calendar and the immoral contents of the plays, which very often staged adultery and other ‘sins’. However, if they had wanted to lure people away from those pagan spectacles, they might have tried offering them Christian entertainment or plays with a moralizing content instead, right? Those kinds of entertainment did appear, but only from the 10th century onwards, in the West. The Byzantine suspicion of the theatrical spectacle was rooted much deeper, not in the specific shape that late antique plays happened to take (although that was felt to be a problem too), but in the very medium of live performance. According to one Church Father, John Chrysostom, theatrical performances exert a corrupting force because of their ambiguous status: they are both real and not real at the same time. They are staged illusions, but as staged and embodied manifestations, those illusions become inseparable from reality. For instance, if an actor is weeping in order to convey sadness, his tears are real, even if the grief is not. Hence, for John Chrysostom, theatrical representations were thought to corrupt reality and affect the spectator negatively, because they have the power to ‘transform’ reality and infuse it with deception. Today, we may call theatrical representations ‘plays’, but for the Church fathers, they could never be ‘just’ games; they had very real and serious consequences.

The Christian hostility towards live performance was the point of departure for my doctoral research on early Byzantine hagiography. The danger that was felt to flow from the blurred borderline between reality and illusion seemed particularly relevant to me in the context of stories about saints who pretended to be someone they were not. One saint named Andrew pretended to be drunk in order to convince others that he was a lunatic and a fool, while he was in reality a most pious man. It appears the author may have been sensitive to the transformative power of illusions, since, out of all the possible methods Andrew could have chosen to be persuasive as a fool, he engaged in one that is characterized by a sharp distinction between the pretended illusion (intoxication) and the hidden truth (sobriety). While Mike Shiner in Birdman, by drinking on stage, tries to make the dividing line between reality and illusion as thin as possible in order to improve his acting, the fact that Andrew only pretends to be drunk helps to keep his real and pretended identities separate. Both make you wonder, nonetheless, about the truth. Is Mike more truthful, or is Andrew? It is surprisingly hard to say… Both characters thus remind us of how fragile something so seemingly self-evident as the truth really is.

False Realness

The year is drawing to a close and so is my adventure in the United States. One of the many things I have learned about this country is that it takes entertainment seriously and is therefore also very good at it. Broadway is one example. The thrill of a Broadway show lies in the high quality of the costumes, decors, and special effects, which are all aimed at transporting the audience to a different world, which looks surprisingly ‘real’. Broadway excels in false realness. If Church Fathers were hostile towards something like that, the modern public certainly enjoys it. At the same time, as much as the musical I saw (see the photo) was trying hard to make the scenes as realistic as possible, the fact that all the characters went through life singing and dancing was a reminder for me that this was not reality after all. Is this why I am not that into musical? Because, when the characters suddenly break out in song, it disrupts my engagement with the illusion? On the other hand, is not the paradoxical coexistence of a realistic presentation and an untruthful content – false realness – precisely what makes this and other forms of modern entertainment (movies, indeed) exciting? In musical, singing is perhaps a deliberate strategy to enhance the cognitive dissonance. It may be that Church Fathers underestimated the human capacity to be immersed into a presentation and to simultaneously maintain an awareness of its non-seriousness. Birdman offers an interesting experiment of what would happen if such a mental duality would prove to be untenable. At the same time, it also critically reflects on modern entertainment by asking how far the paradoxical coexistence of reality and illusion can be pushed before something cracks. Personally, I believe we need illusions. In our imagination, we can freely explore alternative realities, which, instead of fusing with the ‘real’ reality to form an epistemological hot mess, usually offer a foil for our interpretation of the latter. In that sense, Broadway may indeed be about more than entertainment alone.

The year is drawing to a close and so is my adventure in the United States. One of the many things I have learned about this country is that it takes entertainment seriously and is therefore also very good at it. Broadway is one example. The thrill of a Broadway show lies in the high quality of the costumes, decors, and special effects, which are all aimed at transporting the audience to a different world, which looks surprisingly ‘real’. Broadway excels in false realness. If Church Fathers were hostile towards something like that, the modern public certainly enjoys it. At the same time, as much as the musical I saw (see the photo) was trying hard to make the scenes as realistic as possible, the fact that all the characters went through life singing and dancing was a reminder for me that this was not reality after all. Is this why I am not that into musical? Because, when the characters suddenly break out in song, it disrupts my engagement with the illusion? On the other hand, is not the paradoxical coexistence of a realistic presentation and an untruthful content – false realness – precisely what makes this and other forms of modern entertainment (movies, indeed) exciting? In musical, singing is perhaps a deliberate strategy to enhance the cognitive dissonance. It may be that Church Fathers underestimated the human capacity to be immersed into a presentation and to simultaneously maintain an awareness of its non-seriousness. Birdman offers an interesting experiment of what would happen if such a mental duality would prove to be untenable. At the same time, it also critically reflects on modern entertainment by asking how far the paradoxical coexistence of reality and illusion can be pushed before something cracks. Personally, I believe we need illusions. In our imagination, we can freely explore alternative realities, which, instead of fusing with the ‘real’ reality to form an epistemological hot mess, usually offer a foil for our interpretation of the latter. In that sense, Broadway may indeed be about more than entertainment alone.

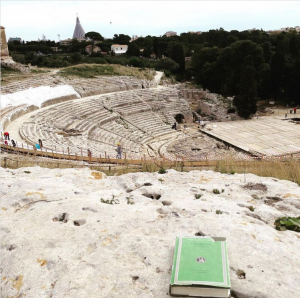

“The Greek novel is, in short, an epic of decadence which plays out easy procedures, exactly those that we see today on the screen, in order to stir emotions: oppositions of good and bad guys, of likable and of supporting characters; and procedures like storms and shipwrecks, and attacks by brigands and pirates, in order to plunge the good into misfortune.” I translate from Georges Dalmeyda’s 1926 French edition of Xenophon of Ephesos’ An Ephesian Story (1st-2nd century CE), one of the five extant Greek novels and often the loser of comparisons to any of the other four, not least for the syncopated rhythm of the narrative. I’m surprised less by his (then common) judgement on the decadence of the ancient novels than by his negative appraisal of the films of his time, since some watershed stuff was in the making: 1925 was the year of Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin, 1927 of Lang’s Metropolis, and in 1928 Buñuel and Dalí would start working on Un chien andalou, not very far from Dalmeyda. Also round the corner was film’s most momentous revolution: talking pictures. Swashbucklers aside (or perhaps included), the frontiers of the thirtysomething-year-old medium were constantly being pushed, and I believe that something similar can be said for Xenophon. Incidentally, what I have in mind is especially germane to film, so I’ll first turn to a contemporary of Dalmeyda who also picked up on the connections between novels and films.

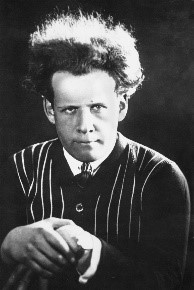

“The Greek novel is, in short, an epic of decadence which plays out easy procedures, exactly those that we see today on the screen, in order to stir emotions: oppositions of good and bad guys, of likable and of supporting characters; and procedures like storms and shipwrecks, and attacks by brigands and pirates, in order to plunge the good into misfortune.” I translate from Georges Dalmeyda’s 1926 French edition of Xenophon of Ephesos’ An Ephesian Story (1st-2nd century CE), one of the five extant Greek novels and often the loser of comparisons to any of the other four, not least for the syncopated rhythm of the narrative. I’m surprised less by his (then common) judgement on the decadence of the ancient novels than by his negative appraisal of the films of his time, since some watershed stuff was in the making: 1925 was the year of Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin, 1927 of Lang’s Metropolis, and in 1928 Buñuel and Dalí would start working on Un chien andalou, not very far from Dalmeyda. Also round the corner was film’s most momentous revolution: talking pictures. Swashbucklers aside (or perhaps included), the frontiers of the thirtysomething-year-old medium were constantly being pushed, and I believe that something similar can be said for Xenophon. Incidentally, what I have in mind is especially germane to film, so I’ll first turn to a contemporary of Dalmeyda who also picked up on the connections between novels and films. Enter Sergei Eisenstein: director, theorist, mega film buff, and, as film buffs among you will know, god of montage. Tasked with making film the medium of the revolutionary working class, from the 1920s onwards he also wrote extensively about film. His essays and books give a good idea of the excitement around the achievements of contemporary film as well as the uncharted territories ahead. Eisenstein knew that in art as in nature nothing is created and everything is transformed, so he had no time for illusions of invention or originality: “It is always pleasing to recognize again and again the fact that our cinema is not altogether without parents and without pedigree, without the traditions and rich cultural heritage of the past epochs.” (232). He looked across media and cultures, absorbing like a sponge any idea that might improve film and get us closer to grasping its nature, from Japanese Kabuki theatre and ideograms to painting (he died when colour films were taking off) and poetry. Nowhere was he keener to acknowledge predecessors than with regards to montage, the technique that ultimately sent him to glory. Particularly famous is an essay of his from ’44 on parallel montage and its masters.

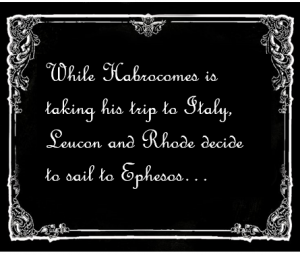

Enter Sergei Eisenstein: director, theorist, mega film buff, and, as film buffs among you will know, god of montage. Tasked with making film the medium of the revolutionary working class, from the 1920s onwards he also wrote extensively about film. His essays and books give a good idea of the excitement around the achievements of contemporary film as well as the uncharted territories ahead. Eisenstein knew that in art as in nature nothing is created and everything is transformed, so he had no time for illusions of invention or originality: “It is always pleasing to recognize again and again the fact that our cinema is not altogether without parents and without pedigree, without the traditions and rich cultural heritage of the past epochs.” (232). He looked across media and cultures, absorbing like a sponge any idea that might improve film and get us closer to grasping its nature, from Japanese Kabuki theatre and ideograms to painting (he died when colour films were taking off) and poetry. Nowhere was he keener to acknowledge predecessors than with regards to montage, the technique that ultimately sent him to glory. Particularly famous is an essay of his from ’44 on parallel montage and its masters. If this were a silent film, which in my mind it is, without changing much to the text, each of these sections could be the title card before the respective scene. Notice too the geographical red thread that connects the sections, each containing the location of the next one. My favourite cut is when the camera shows Ephesos in Habrocomes’ mind and moves seamlessly to the flashback on the parents therein. Some have ascribed so hectic a prose either to sloppy writing or the abridgement from an originally longer version, but I’ve asked Xenophon and he said no, it’s parallel montage. And indeed it’s the visual that helps readers navigate the cross-cutting. When Habrocomes’ action is resumed a little later (“Habrocomes, meanwhile, set sail from Sicily”), we find him in the same shot as his last one (the “take a boat from Sicily to Italy” from before). The same goes for Anthia. We see a shot of her in bed just before we cut to Habrocomes setting sail, and after a bit of him sailing and whining we come back to her, still in bed: “So he was lamenting and suffering from his labours. Meanwhile Anthia had a dream as she slept in Taras.”

If this were a silent film, which in my mind it is, without changing much to the text, each of these sections could be the title card before the respective scene. Notice too the geographical red thread that connects the sections, each containing the location of the next one. My favourite cut is when the camera shows Ephesos in Habrocomes’ mind and moves seamlessly to the flashback on the parents therein. Some have ascribed so hectic a prose either to sloppy writing or the abridgement from an originally longer version, but I’ve asked Xenophon and he said no, it’s parallel montage. And indeed it’s the visual that helps readers navigate the cross-cutting. When Habrocomes’ action is resumed a little later (“Habrocomes, meanwhile, set sail from Sicily”), we find him in the same shot as his last one (the “take a boat from Sicily to Italy” from before). The same goes for Anthia. We see a shot of her in bed just before we cut to Habrocomes setting sail, and after a bit of him sailing and whining we come back to her, still in bed: “So he was lamenting and suffering from his labours. Meanwhile Anthia had a dream as she slept in Taras.” 3. will come and live in Belgium, work together with the other team members, and contribute to a pleasant and stimulating atmosphere;

3. will come and live in Belgium, work together with the other team members, and contribute to a pleasant and stimulating atmosphere;

Despite my love of Tacitus, the sheer novelty of ancient fiction won out. After the Origins course, I did my undergraduate dissertation on the Roman novels of Apuleius and Petronius, and when I moved to Cambridge for postgraduate study I continued with novels, moving increasingly over to the Greek novels of Chariton, Xenophon, Longus, Achilles Tatius, and Heliodorus. My PhD thesis looked at concepts of fiction in these texts, not through narratological readings, but as a contextual phenomenon which reflected both earlier philosophical and rhetorical discussions of fiction and also contemporary imperial practices. In other words, I wanted to understand ancient novelistic fiction as a product of the literary cultures of the Roman empire, and to think harder about fiction as a conscious choice rather than just a naturalised part of the novelistic genre as understood by modern readers.

Despite my love of Tacitus, the sheer novelty of ancient fiction won out. After the Origins course, I did my undergraduate dissertation on the Roman novels of Apuleius and Petronius, and when I moved to Cambridge for postgraduate study I continued with novels, moving increasingly over to the Greek novels of Chariton, Xenophon, Longus, Achilles Tatius, and Heliodorus. My PhD thesis looked at concepts of fiction in these texts, not through narratological readings, but as a contextual phenomenon which reflected both earlier philosophical and rhetorical discussions of fiction and also contemporary imperial practices. In other words, I wanted to understand ancient novelistic fiction as a product of the literary cultures of the Roman empire, and to think harder about fiction as a conscious choice rather than just a naturalised part of the novelistic genre as understood by modern readers.

hiding in some bushes so as not to be seen, she heard everything they said and saw all they did.” This happens three-quarters into the novel, after the narration of all the games played by Daphnis and Chloe, including their attempt at sex. When we read this, Lykainion has been in the novel only for a few lines, but we realise, retroactively, that she’s been in the story for a while (“She saw Daphnis every day…”). It’s a little spooky, because up until that moment we thought we were the only ones with spying privileges, but now we find out that she was there with us, or perhaps we with her. No filmmaker could pass a peeping-Tom opportunity like this, and in fact Laskos anticipates Lykainion’s arrival and punctuates the games of Daphnis and Chloe with shots of her, to remind us that we’re watching them from her point of view. Of course she is a predator (the name means ‘she-wolf’) and will get what she wants (Daphnis), but it’s for the greater good of his learning what he and Chloe have been searching for. Laskos captures well her ambivalent participation in the story and invites us to reflect on ours.

hiding in some bushes so as not to be seen, she heard everything they said and saw all they did.” This happens three-quarters into the novel, after the narration of all the games played by Daphnis and Chloe, including their attempt at sex. When we read this, Lykainion has been in the novel only for a few lines, but we realise, retroactively, that she’s been in the story for a while (“She saw Daphnis every day…”). It’s a little spooky, because up until that moment we thought we were the only ones with spying privileges, but now we find out that she was there with us, or perhaps we with her. No filmmaker could pass a peeping-Tom opportunity like this, and in fact Laskos anticipates Lykainion’s arrival and punctuates the games of Daphnis and Chloe with shots of her, to remind us that we’re watching them from her point of view. Of course she is a predator (the name means ‘she-wolf’) and will get what she wants (Daphnis), but it’s for the greater good of his learning what he and Chloe have been searching for. Laskos captures well her ambivalent participation in the story and invites us to reflect on ours. Snow globe narrative

Snow globe narrative The film makes some spectacular self-sabotaging choices, number one of which has to be bringing forward the final recognition of Daphnis by his real parents, with obvious anticlimactic repercussions on the ending. But this allows a

The film makes some spectacular self-sabotaging choices, number one of which has to be bringing forward the final recognition of Daphnis by his real parents, with obvious anticlimactic repercussions on the ending. But this allows a  Nikos Koundouros’ Young Aphrodites

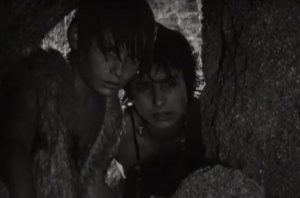

Nikos Koundouros’ Young Aphrodites Young Aphrodites (terrible title) is spoken, but with only about 200 lines in 90 minutes you would have thought this the silent film and not Laskos’, which indulges in pretty hefty dialogue intertitles. Everything is conveyed through the filming of eyes and body movements, and one of the things that make the film exceptional are the games of Chloe and Skymnos in a rugged rocky landscape by the sea, a clearly liminal and symbolic location. There’s something about the rawness of their chases, the frustration of their stares, the hopelessness of their promises to one another, which is at the same time warming and tragic. Longus is nowhere near as effective at conveying the protagonists’ pains. They are the ones who carry the burden of all the different structural clashes and, too small and unguided, are crushed by it (their totem bird is a crucified pelican). A distorted version of the Lykainion look serves Koundouros well in playing out all of this. It is used to show the pair spy on Arta and Tsakalos having sex in a cave, looking at what may await them as well (left). But it’s a spectacle that scars them, offering no answer they can understand and instead throwing them into an unhappy confusion. It is also used to show Skymnos observing the excruciating rape of Chloe by Lykas (below). The difference between the shots of Lykainion and Skymnos sums up the different keys of the films as well as the viewers’ position. Young Aphrodite is an unforgiving, almost neorealist take on the story of Daphnis and Chloe, with no room for idealisation. It’s as if Koundouros wanted to test part of the plot against real life (as real as imagined 200BC Greece can be), and part of me wishes he hadn’t.

Young Aphrodites (terrible title) is spoken, but with only about 200 lines in 90 minutes you would have thought this the silent film and not Laskos’, which indulges in pretty hefty dialogue intertitles. Everything is conveyed through the filming of eyes and body movements, and one of the things that make the film exceptional are the games of Chloe and Skymnos in a rugged rocky landscape by the sea, a clearly liminal and symbolic location. There’s something about the rawness of their chases, the frustration of their stares, the hopelessness of their promises to one another, which is at the same time warming and tragic. Longus is nowhere near as effective at conveying the protagonists’ pains. They are the ones who carry the burden of all the different structural clashes and, too small and unguided, are crushed by it (their totem bird is a crucified pelican). A distorted version of the Lykainion look serves Koundouros well in playing out all of this. It is used to show the pair spy on Arta and Tsakalos having sex in a cave, looking at what may await them as well (left). But it’s a spectacle that scars them, offering no answer they can understand and instead throwing them into an unhappy confusion. It is also used to show Skymnos observing the excruciating rape of Chloe by Lykas (below). The difference between the shots of Lykainion and Skymnos sums up the different keys of the films as well as the viewers’ position. Young Aphrodite is an unforgiving, almost neorealist take on the story of Daphnis and Chloe, with no room for idealisation. It’s as if Koundouros wanted to test part of the plot against real life (as real as imagined 200BC Greece can be), and part of me wishes he hadn’t.

I went through the process of applying for a Visa with the US embassy in Brussels before, in 2019. The whole experience was frustratingly complex even then. To make matters worse, on the very day of my appointment at the embassy, a fire had broken out in a tunnel close to Brussels Central, interrupting all train traffic. But a few detours could not keep me from my goal. I eventually managed to make all necessary preparations and left for a two-month research stay in Washington DC, which turned out to be one of the best academic experiences of my career so far. (See image to the right: the library of Dumbarton Oaks in Washington DC, currently closed due to Covid – picture taken in 2019.) The plan was to go back for further research and, this time, the envisaged stay is twelve months. However, this time, what stands in between me and my research plans is not a fire, but a virus.

I went through the process of applying for a Visa with the US embassy in Brussels before, in 2019. The whole experience was frustratingly complex even then. To make matters worse, on the very day of my appointment at the embassy, a fire had broken out in a tunnel close to Brussels Central, interrupting all train traffic. But a few detours could not keep me from my goal. I eventually managed to make all necessary preparations and left for a two-month research stay in Washington DC, which turned out to be one of the best academic experiences of my career so far. (See image to the right: the library of Dumbarton Oaks in Washington DC, currently closed due to Covid – picture taken in 2019.) The plan was to go back for further research and, this time, the envisaged stay is twelve months. However, this time, what stands in between me and my research plans is not a fire, but a virus. Yet, the meaning of miracles was not always straightforward. Since they are the product of an act of interpretation, they are open to different forms of understanding and (in the eyes of some) misunderstanding. Jesus and the apostles were frequently charged with accusations of magic by opponents of the new religion. This was an effective strategy to discredit them as well as the power they were perceived to be invested with, and therefore discredit the entire religion they sought to promote. For magic had sinister connotations: in the eyes of the broad public, it was typically practiced by outsiders and charlatans.

Yet, the meaning of miracles was not always straightforward. Since they are the product of an act of interpretation, they are open to different forms of understanding and (in the eyes of some) misunderstanding. Jesus and the apostles were frequently charged with accusations of magic by opponents of the new religion. This was an effective strategy to discredit them as well as the power they were perceived to be invested with, and therefore discredit the entire religion they sought to promote. For magic had sinister connotations: in the eyes of the broad public, it was typically practiced by outsiders and charlatans. As my research about ambiguity in the ancient world got me thinking about uncertainty today, it inevitably made me reflect on the uncertainty I am personally facing with regard to my academic adventures abroad. It is undeniable that the pandemic has brought more uncertainty into my life than before. Nonetheless, another way to think about this is that the current crisis did not necessarily create new challenges but made the existing ones rise to the surface, rendering them more acute. Perhaps the uncertainty was always there, but I failed to notice it because I was too busy making plans, by-passing uncertainty before it could even manifest itself. In other words, there is an opportunity here to think about how we go about our lives. (Or, to use Ellen’s words again, “uncertainty carries an inherent potential”—coming at this from my own academic corner, I can only agree.) What does it mean to go abroad for research, for instance? And what does that contribute to my personal narrative; how is it meaningful? If anything, the crisis has taught me to be more self-aware about my choices, as well as about the fact that not everything is under my control. What I can control, is the way in which I understand and interpret the uncertainty and ambiguity I find all around me.

As my research about ambiguity in the ancient world got me thinking about uncertainty today, it inevitably made me reflect on the uncertainty I am personally facing with regard to my academic adventures abroad. It is undeniable that the pandemic has brought more uncertainty into my life than before. Nonetheless, another way to think about this is that the current crisis did not necessarily create new challenges but made the existing ones rise to the surface, rendering them more acute. Perhaps the uncertainty was always there, but I failed to notice it because I was too busy making plans, by-passing uncertainty before it could even manifest itself. In other words, there is an opportunity here to think about how we go about our lives. (Or, to use Ellen’s words again, “uncertainty carries an inherent potential”—coming at this from my own academic corner, I can only agree.) What does it mean to go abroad for research, for instance? And what does that contribute to my personal narrative; how is it meaningful? If anything, the crisis has taught me to be more self-aware about my choices, as well as about the fact that not everything is under my control. What I can control, is the way in which I understand and interpret the uncertainty and ambiguity I find all around me. In

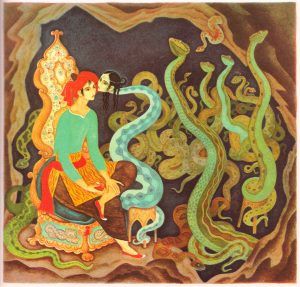

In  Even just from these brief snapshots of the broader mosaic which is the Nights, it’s clear that these narratives offer a number of points of connection with the Greek novel, but nothing like conclusive proof of a relationship between the two. The themes treated in both texts, such as erotic desire, gender roles, and travel into fantastical lands are so general as to testify more to universal themes in narrative rather than a specific relationship between these two corpora. After all, it’s clear that given the diversity of traditions which underlie both the ancient Greek novel and the One Thousand and One Nights there doesn’t need to be a direct relationship between the two for them to engage with similar motifs and concerns.

Even just from these brief snapshots of the broader mosaic which is the Nights, it’s clear that these narratives offer a number of points of connection with the Greek novel, but nothing like conclusive proof of a relationship between the two. The themes treated in both texts, such as erotic desire, gender roles, and travel into fantastical lands are so general as to testify more to universal themes in narrative rather than a specific relationship between these two corpora. After all, it’s clear that given the diversity of traditions which underlie both the ancient Greek novel and the One Thousand and One Nights there doesn’t need to be a direct relationship between the two for them to engage with similar motifs and concerns.