— This blog post was written by Dr Claire Rachel Jackson, postdoctoral researcher in the Novel Echoes research group.

Some things change, some things don’t. At the start of 2020, just as our Novel Echoes project got off the ground, Covid-19 struck and Belgium went into lockdown. At the start of this academic year, just as soon as we were all together again…Belgium went back into lockdown. It’s hard not to have a sense of déjà vu about all of this, especially with yet another nail-biting US presidential election and more tense Brexit negotiations taking over the headlines. At the moment, life seems to ricochet between unstructured uncertainty and the predictable rhythms of lockdown, teleworking, and so forth.

People need stories more than bread itself

One pleasing bit of continuity over this period has been the Novel Echoes reading group, where we meet to analyse a text with relevance to the wider aims of the project. Thanks to the varying corona restrictions, we’ve been seesawing between meeting online, then in persona, then online again (and likely for the foreseeable future), meaning that our now-prohibited in-person meetings have taken on a near-mythical status. (As my colleague Nick put it, we’ll always have Rozier room 2.3…) Despite these difficulties, however, our commitment to meeting regularly, reading our way through a text, and building up a sense of its themes and context adds some certainty to an otherwise uncertain time.

One pleasing bit of continuity over this period has been the Novel Echoes reading group, where we meet to analyse a text with relevance to the wider aims of the project. Thanks to the varying corona restrictions, we’ve been seesawing between meeting online, then in persona, then online again (and likely for the foreseeable future), meaning that our now-prohibited in-person meetings have taken on a near-mythical status. (As my colleague Nick put it, we’ll always have Rozier room 2.3…) Despite these difficulties, however, our commitment to meeting regularly, reading our way through a text, and building up a sense of its themes and context adds some certainty to an otherwise uncertain time.

Our text of choice has been the One Thousand and One Nights, the miscellany of narratives also known in English as the Arabian Nights, and what follows are my initial musings on reading the text together.[1] The overarching narrative involves Shahrazad telling stories to her husband in order to postpone her death, as his desire to hear the next story keeps him from getting bored and uxoricidal. (The story goes that after his first wife cheated on him, the tyrant married a new woman every night and murdered her in the morning before she could betray him, a mix of unpleasant sexual politics and incredible quantities of homicide). Within this framework, however, the Nights consists of a variety of inset narratives, composed at different times, from different locations, and covering a multitude of topics. Given the remit of the Novel Echoes project to investigate the early reception of the ancient novel throughout late antiquity and beyond, a compilation like the Nights which brings together a variety of post-classical fictions is an obvious flashpoint for these questions.

But if the Nights is an important landmark in novelistic reception, it is also a major problem. The reception of the Greek novel in what was the Eastern half of the Roman empire and beyond has been asserted for a long time, but pinning down the specifics has proved trickier. Most prominently, Tomas Hägg and Bo Utas have shown that the eleventh-century Persian epic poem Wamiq u ‘Adrha derives from the barely-extant first-century novel Metoichus and Parthenope, which seems to have been well-known due to live performances in Syriac-speaking regions.[2] But does this testify to the prevalence of the novel as a genre, or to the limited reception of single texts? Can we interpret this more widely to find out something about the continuity of fictional traditions, a single thread unspooling across time periods and cultural contexts – or is this simply a reflection of specific and isolated influences?

This question was raised as far back as the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, when theorists such as Pierre-Daniel Huet and Clara Reeve saw both the ancient novel and Eastern fables as a key part of the genealogy of the contemporary French roman and early modern English novel.[3] As such, the Nights stands at a paradoxical crossroads: if the ancient novel as a genre has any significant purchase in the fictional traditions of the Middle East (very widely defined), surely there would be some evidence of it in the miscellany of tales which makes up the Nights. Conversely, the tradition of placing the Nights into a continuous history of fiction, in which all novels, romances, and sagas across chronological periods and cultural contexts can be linked, undercuts that possibility. After all, if a fiction is a universal trend, can we really trace any direct cross-cultural influence? The Nights epitomises these issues, but offers no easy answers.

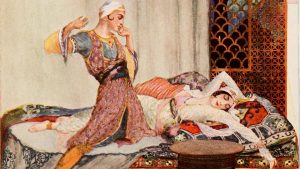

My story is of such a marvel!

This is exemplified by the story of Budur and Kamar, which has been described by von Grunebaum as particularly rich in novelistic motifs.[4] In its outline the narrative is distinctly novelistic: the progression of mutual infatuation between two exceptionally beautiful young people, marriage, separation, and reunion has antecedents across the extant ancient novelistic corpus. But while the generalities track, the specific details are more complicated. The protagonists’ initial meeting is not a chance encounter at a festival, as the novelistic stereotype goes, but they instead suddenly appear in bed next to each other, having been brought together magically by a pair of mischievous jinn. After this initial meeting, however, they are returned to their homelands, where no-one believes their story (quite reasonably), and they begin to waste away with longing for each other. Only Budur’s foster-brother recognises her disease as love-sickness and brings the two together by disguising Kamar as an astrologer who arrogantly promises to cure Budur without even seeing her. Kamar writes a letter to the princess, ostensibly a healing spell but in actuality a letter explaining who he is, and includes her ring, the physical proof of their night together.[5]

The prince folded this letter and, slipping the ring inside it,

sealed it and handed it to the eunuch. The slave gave it at once to his mistress, saying:

“Madam, there is behind your curtain a certain young astrologer, so audacious that he pretends to be able to cure folk without seeing them.

He has sent this paper to you.”

No sooner had the princess opened the paper than she recognised her ring

and cried aloud; pushing aside the eunuch, she ran through the curtain and knew her lover.

Then it might have been thought that she was really mad; she threw herself upon his neck,

and they kissed like two doves which had been long away from each other.

Numerous novelistic parallels can be adduced here: love at first sight; love-sickness which is misunderstood as ordinary disease by almost everyone; a helper who stands somewhere between a philosophical advisor and a manipulative charlatan; recognition following their separation.[6] But none of this is exclusively novelistic – in many ways, the archetype for this kind of long-enduring love, disguise and protracted recognition is the relationship between Odysseus and Penelope in the Odyssey. If these parallels are proof of some kind of connection between the Nights and the Greek novel, it’s undeniably general, based on thematic interests and motifs rather than specifics.

I took in anything that was new and strange

This also demonstrates the wider issues invoked by this text, especially for Classicists. As a traditionally-trained Classicist, I’m confident with Ancient Greek and Latin traditions ranging from the archaic period to Late Antiquity – or at least, I know where to go to get answers. But this pushes me beyond the limits of my knowledge. The Nights has a complex transmission history, has likely been compiled from different sources at different times, and different parts of the narrative have been added at various points ranging from the eighth to the thirteenth centuries.[7] If I see a link between the Greek novel, the genre I’ve spent my entire academic life studying, and the Nights, a text I’m looking at in isolation from its cultural and literary contexts, might there be traces of a genuine connection there? Or might it be instead be me importing my own perspective onto a text that doesn’t fit the framework through which I’m used to viewing literature? As the old saying goes: ‘when you have a hammer, everything looks like a nail’. Or, more accurately, when you have a variety of extant and fragmentary Greek novels and an academic who probably should get out more, all other fictional texts can end up looking like variations of the ones they know best.

So given all these difficulties, why should we look at the Nights? The flipside of these drawbacks is that studying a text from a totally different cultural context exposes the limitations of this viewpoint. As a discipline, Classics has historically been particularly interested in direct relationships between texts, but a work like the Nights, which is a literarily sophisticated, chronologically sprawling miscellany, challenges that model of intertextuality. For those of us who work on texts conventionally aligned with a so-called Western literary tradition, looking at this kind of text compels us to re-examine our assumptions about the nature of ancient reception and the utility of a Greco-Roman framework for exploring other literary contexts. While it is likely impossible to conclusively prove or disprove a direct connection between the Nights and the Greek novel, placing the two in dialogue forces us to confront these kinds of tensions and reconsider our own perspective on and vested interests in such a relationship.

TO BE CONTINUED…

[1] Many different titles and transliterations of names have been used to discuss the Nights in English – my choices here reflect the translations I’ve used rather than any ideological or linguistic preferences.

[2] Tomas Hagg and Bo Utas (2003) The Virgin and her Lover: Fragments of an Ancient Greek Novel and a Persian Epic Poem, Leiden. See also Daniel King (2018) ‘Translation’ in Scott McGill and Edward J. Watts (eds.) A Companion to Late Antiquity, Hoboken NJ: 523-38.

[3] Pierre-Daniel Huet (1670) Lettre-traité sur l’origine des romans; Clara Reeve (1785) The Progress of Romance. Huet’s work can be called the first history of fiction and traces a direct link between the Greek novel, building on Eastern prototypes, and the French roman, whereas Reeve’s sees similar origins for the novel but draws a sharper distinction between the old-fashioned ancient romance and the contemporary English novel.

[4] Gustave E. von Grunebaum (1942) ‘Greek Form Elements in the Arabian Nights’, Journal of the American Oriental Society 62.4: 277-92.

[5] This translation is taken from E. P. Mathers (1986) The Book of the Thousand and One Nights: Rendered into English from the Literal and Complete French Translation of Dr J. C. Mardrus, London and New York, Vol. 2.

[6] All of these motifs can be seen in more than one novel, but particularly visible here is the recognition via letter as seen in Achilles Tatius’ Leucippe and Clitophon, and via voice in Chariton’s Callirhoe: on this see in particular Silvia Montiglio (2013) Love and Providence: Recognition in the Ancient Novel, Oxford. The diagnosis of love-sickness and medico-magical treatment recalls Heliodorus’ Aithiopika, whereas Longus’ Daphnis and Chloe dramatises the protagonists’ love-sickness as a mystery to them in particular. The advisor skilled in deception and trickery brings to mind in particular Heliodorus’ Calasiris, whose intentions have been long debated in scholarship: Jack Winkler’s (1982) ‘The Mendacity of Kalasiris and the Narrative Strategy of Heliodoros’ Aithiopika’, YCS 27: 93-158 remains a classic on this subject.

[7] This transmission history is also complicated by the role of European translators who popularised the Nights from the eighteenth century onwards, who appropriated and reworked the Nights to suit their own purposes and assert their own cultural cachet within the imperialist contexts of the period. See Paulo Lemos Horta (2017) Marvellous Thieves: Secret Authors of the Arabian Nights, Cambridge MA on this (and my thanks to my fellow postdoctoral researcher, Simon Ford, for this reference).