— This blog post was written by Dr Mara Nicosia, postdoctoral researcher in the Novel Echoes project.

This story does not start on a battlefield, where valiant heroes are fighting, killing, and plotting to burn down a whole city, nor does it tell the deeds of a group of men, lost at sea, doomed to roam around for ten years. However, it does start at one famous setting from Odysseus’ nostos, namely at the feet of the moody volcano Etna, where the landscape is as black as the lava that covers it. I was born and raised there, although I left to seek knowledge at the feet of that other volcano that once famously covered in burning lapilli a whole city. I studied oriental languages in Catania first and Naples later, and from the University of Naples “L’Orientale” I got my Ph.D.

When I came to Ghent last year, I had already done my fair share of moving around Europe, having lived in both Paris and Madrid. During my travels, I kept on working on Semitic languages, eager to share my research with as many unfortunate souls as possible. The study of these languages in general, and my research subject in particular, are not too common or well-known; therefore, I always share as much as I can: through talks, classes, or blog posts, I try to raise awareness of the existence of “roads less travelled” and languages less famous but equally important. The occasion to teach my research presented itself when I was offered to co-teach a first-semester BA-course on Ancient Rhetoric: having worked for many years on Syriac and Arabic rhetoric, I immediately agreed. However, it was only when I started preparing for the lectures that I realized that I would have to start from the very beginning: what are Semitic languages? Where are they spoken?

Since the students in my course do not read Semitic writings or have much of an idea of what happened in the Ancient and Medieval Near East, and I had no adequate course book, I decided to write an (informal) handbook myself. I have always had a hard time cherry-picking the really important subjects from the pool of information that I gathered over the past six years, but one thing I knew for sure was that I would have to start from zero, from the “where, when, how, and what”. I started to line up data on the history, writing system, attestations, and number of speakers of all the Semitic languages, both ancient and modern, taking care of giving an overview of the vastness of the topic. Needless to say, the students, who came from various disciplines, from modern languages and literatures to communication, classics, and archaeology, were overwhelmed by my first lesson. Nevertheless, they all turned up for the next class!

The first part of the journey, or: The one where I went from “I think they hate this” to “I think they are listening”

I felt that that was the moment our journey together really began. My first action was to prepare the setting: after the death of Alexander the Great, in 323 BCE, the Greek-ruled Seleucid Empire (321-64 BCE) took over a large part of it and started ruling over the Syrian and Mesopotamian regions, among many others. In the 2nd century BCE, this large imperial compound lost control over a region called Osrhoene, where a local ruling dynasty, the Abgarids, was established (133 BCE). However, with time, the political geography around the Osrhoene changed and the region found itself squeezed between the Parthian Empire on the eastern borders and the Roman Empire on the western. Eventually, the latter succeeded in declaring Edessa, the capital city of Osrhoene, a Roman colonia in 212 CE. The Romans did not impose a restrictive language policy on the area, allowing the pre-existing massive Greek influence to keep acting undisturbed on the Near Eastern Aramaic-speaking communities. Greek was the lingua franca of the eastern provinces of the Roman Empire, whereas Latin was employed in military and legal matters. The local language of the city of Edessa (modern-day Şanlıurfa, in south-eastern Turkey), was a variety of Late Aramaic, which came to be known as Syriac: Syriac turned into the literary and religious language of a large branch of Eastern Christianity and reached as far as India and China.

The frame itself sounds engaging, doesn’t it? What is even more catchy is that, despite the massive influence exerted by Greek sciences, philosophy, literature, and educational pattern, even though rhetoric was one of the basic subjects of Syriac education, even though classical rhetorical devices were employed from the very beginning of Syriac literature… we have to wait until the 9th century to learn how the subject was taught and to have a proper handbook of rhetoric in Syriac. But the surprises are not over: although Syriac rhetoric was imbued with Greek models, it was not based on Aristotle’s Rhetoric! Rhetoric in Syriac followed an autonomous, well-established, and highly syncretic tradition: the author of our 9th-century handbook, Antony of Tagrit, based his text on both the pagan and the Christian past and he quoted both Greek and Syriac authors. More importantly, Antony’s handbook is the only Syriac text in which we find the translation of two excerpts from Heliodorus’ Aethiopica. Wait, there is more: although the vast majority of Aristotle’s philosophical essays were translated into Syriac, we do not have a manuscript with a Syriac translation of Rhetoric. It existed for sure, but we do not have it.

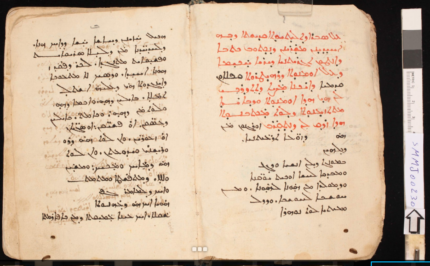

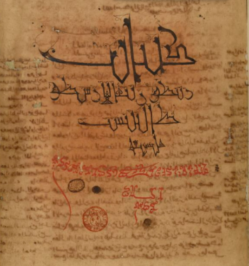

I decided to show my students a sample of Syriac manuscripts of Antony of Tagrit’s Rhetoric. I knew they could not read them, but I had an ace up my sleeve: the oldest of these manuscripts is kept in an Egyptian monastery, surrounded by the sands of the desert, and my sister (who is incidentally a colleague of mine) managed to visit it a few months earlier. I showed many of the pictures she had taken, we chatted about the history of the transmission of Syriac manuscripts, wandered around monastic libraries, and, all of a sudden, I realized that we had reached our first harbor safely. I came to realize that my students were intrigued and wanted to know more, although until the day before they had no clue of the existence of these topics. It was time to rest and let all the information settle down to prepare for the last part of our journey.

The second part of the journey or: The one with the final battle and the reaching of the destination

It was now time to sail toward the Arab side and I feared I would lose helm control. I have always struggled with Medieval Arabic philosophy, and I knew my class would struggle too. To ease the topic on all of us, I decided to take the scenic route and started our journey from the core of the Arabian Peninsula, where Old Arabic varieties are attested from the 3rd century CE. I took them to meet the Prophet Muḥammad, follow his conquests, and witness the expansion of the ʼUmmayyad caliphate first and the ʽAbbasid caliphate after. It is during this latter reign that we encountered the Greek-to-Arabic translation movement, a moment of cultural splendor during which an imposing number of Greek texts were translated into Arabic. However, we learned that these translations were realized through Syriac intermediaries, and discovered that it is thanks to the early-11th-century manuscript of the Arabic version of Aristotle’s Rhetoric that we know of the existence of a Syriac version. Isn’t it fantastic? The Arab editor stated that he used two Arabic translations and a Syriac one to put together his version!

We then turned to the commentary tradition and encountered the works of Avicenna (ca. 970-1037) and Averroes (1126-1198). We discussed how the technical vocabulary of rhetoric changed with time, and how it went from being full of loanwords from Greek (via Syriac) to being completely Arabized. In the same way, the contents progressively got more and more target-oriented, with examples coming from the Quran. It was bumpy sailing, but somehow, we managed to see the end of it. When we were finally spotting land from afar, we indulged a few more moments to read and compare a handful of passages from some of the texts we had mentioned. I was particularly delighted by the subsequent discussion since, despite my unsteady lead, my students offered me clever points of view and hypotheses! I was amazed by the power of Near Eastern rhetoric to bring modern students together, despite their former lack of training on the matter.

When the course finished, we finally landed by the time of the Christmas holidays, and the students were safely returned to their homes. I realized there is hope for lesser-known subjects like mine and that we should not stop teaching them. These students have restored my hopes for the future of my discipline and I am glad I took this journey with them. I look forward to the next chapter, the one where I take a new class on a new trip, hoping to always have the wind in our back and the favor of the gods.