This guest blog was written by MA student Ischa Beernaert, as part of his assessment for the UGent MA course ‘Gender and antiquity’, lectured by our research coordinator Evelien Bracke and inspired by a guest lecture by postdoctoral researcher Julie Van Pelt.

September 22nd 2023 – I went to see a performance at the KVS (Royal Flemish Theatre) in Brussels by Carolina Bianchi, a Brazilian director, playwright and actress based in Amsterdam. The title of the work: ‘The Bride and the Goodnight Cinderella’ or originally ‘A Noiva e o Boa Noite, Cinderela’.

The play starts off with Bianchi stepping onto the stage, armed with a big binder. She sits down at a tiny desk, pours herself a drink, takes a nip and starts delving into the contens of the binder: five-hundred pages of research that she conducted for the sake of her performance on the topic of femicide, sexual violence and anti-female terror. The material incorporated both fictional narratives and real, lived experiences, drawing from the stories and testimonies of women who experienced sexual assault; through history and space, from characters of Boccacio’s Decamerone to a Brazilian football player who had his girlfriend dismembered and fed to his rottweilers in 2010. [1] Bianchi skillfully narrates these different stories and so weaves a compelling and heart-wrenching tapestry of female, sexually mutilated bodies and corpses. The red thread through this narrative tapestry is the story of an Italian performance artist called Giuseppina Pasqualino di Marineo (also known as Pippa Bacca) which she starts recounting after having sipped from her drink again.

The play starts off with Bianchi stepping onto the stage, armed with a big binder. She sits down at a tiny desk, pours herself a drink, takes a nip and starts delving into the contens of the binder: five-hundred pages of research that she conducted for the sake of her performance on the topic of femicide, sexual violence and anti-female terror. The material incorporated both fictional narratives and real, lived experiences, drawing from the stories and testimonies of women who experienced sexual assault; through history and space, from characters of Boccacio’s Decamerone to a Brazilian football player who had his girlfriend dismembered and fed to his rottweilers in 2010. [1] Bianchi skillfully narrates these different stories and so weaves a compelling and heart-wrenching tapestry of female, sexually mutilated bodies and corpses. The red thread through this narrative tapestry is the story of an Italian performance artist called Giuseppina Pasqualino di Marineo (also known as Pippa Bacca) which she starts recounting after having sipped from her drink again.

Pippa Bacca and female body-performance

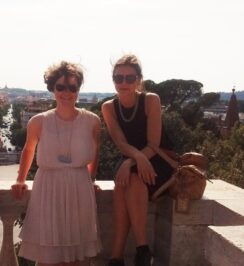

In 2008, on International Women’s Day (8th of March), together with her trusted friend and fellow artist Silvia Moro, Pippa Bacca embarked on a performance called “Brides on Tour”. The performance consisted of hitchhiking (separately) from Milan to Tel-Aviv through several war-torn Balkan countries while wearing white wedding dresses. The aim was to celebrate a symbolic marriage between peoples yearning for peace, represented and facilitated by th

e two brides who offer themselves as messengers of this marriage, sealed by trust. On the road, the two performed symbolic acts and gestures with the women that they would encounter, for example washing their feet or embroidering new elements onto their wedding dresses together. The struggle of women in wartime was the focal point of their journey.

The premise of “Brides on Tour?” was: if one has faith in humanity, if one trusts, one is rewarded for it. This had ultimately led Pippa to get into the car of her own murderer. While Silvia Moro successfully completed the journey, Pippa Bacca was tragically raped and killed in Gebze (Turkey) during the third week of the performance.

A sentence from the press release that was issued by the artists themselves before their actual departure is in many ways telling for the underlying ideas of the performance: “La scelta del viaggio in autostop è una scelta di fiducia negli altri esseri umani, e l’uomo, come un piccolo dio, premia chi ha fede in lui.” “The choice to hitchhike is a choice of trust in other human beings, and man, like a small god, rewards those who have faith in him.” (From the press release of Pippa and Silvia’s departure on March 8, 2008, my translation.)

Not only does this sentence expose the definite Christian undertone of the endeavor, it also shows how the performers were very aware of the physical danger that they would put themselves through. The ‘reward’ of the ‘piccolo dio’ being a safe passage to Tel Aviv. The imminent physical danger was essential to Bacca’s overarching message of trust and the choice to undertake the journey in a wedding dress, symbol of bodily integrity and purity, even added to this matrix of physical danger. Bacca and Moro consciously and very aware of the fact that their political and social commentary would not work otherwise, put their bodies on the line, with tragic femicide as the result.

Carolina Bianchi frames Pippa Bacca’s performance within a larger network of feminist/female performance-art and artists which grew during the ‘60s and ‘70s in the wake of the second wave of feminism and postmodernism. In an analysis of this artistic sub-genre, Forte defines it as a movement wherein ‘[…] women use[d] performance as a deconstructive strategy to demonstrate the objectification of women and its results.’ [2] Central to this act and to this strategy was the physical body of the performing woman. A lot of the performances which would later be considered feminist performance-art put the concrete female body as the central point of investigation within their performance. The artists put

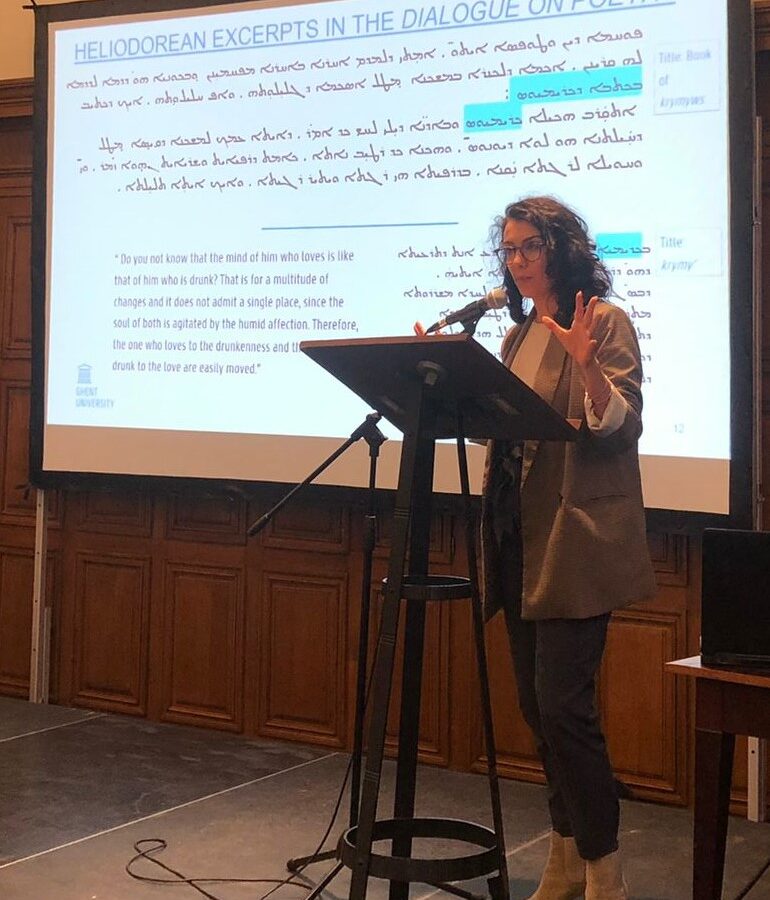

their own bodies at risk in order to uncover the underlying gendered politics which govern the view of the female: their own bodies become the evidence. [3] Another specific feature of the female performance art is the blurring of the distinction between reality and performance as the case of Pippa Bacca painfully shows. An example of such a performance is ‘Rhythm 0’ by Marina Abramović. In this 6-hour performance an audience was invited to do whatever they wished to the body of Ambramović, using seventy-two objects (ranging from feathers to a gun).

Art critic Thomas McEvilley was present at a showing of the piece and in a testimony [4] he recounts how the audience stripped Ambramović from her clothes, slashed her skin with a razor, how they committed all sorts of sexual assaults and how someone even pointed a loaded gun at Ambramović’s head before being stopped by other members of the audience. Further examples of feminist body-performances are ‘Rape Scene’ by Cuban artist Anna Mendieta and ‘Action Pants:Genital Panic’ by Austrian artist Valie Export. [5]

All these female artists willingly expose themselves to real (sexual) violence, misogyny and possibly even death. In doing so they problematize the sexual violence itself, the ‘male gaze’ [6], the objectification of women and ultimately, emicide. In a similar way Pippa Bacca’s performance unveiled these underlying structures. “Seguendo le orme delle artiste degli anni ‘60 e ’70 Bacca si è messa in gioco in una rappresentazione autentica di corposoggetto e non ha avuto paura di esporlo, di condividerlo, di offrirlo in una eucaristia politica che ha i toni dell’enunciazione e non della contestazione.” “Following in the footsteps of the artists of the 1960s and 1970s, Bacca put herself on the line in an authentic representation of the body and was not afraid to expose it, to share it, to offer it in a political Eucharist that has the undertones of enunciation and not of conflict.” (Giulia Di Santo – Il corpo di Pippa Bacca, 2022, p. 485, my translation)

In one gulp, Bianchi eventually finishes the glass she poured herself at the beginning of the performance and with it she finishes the story of Pippa Bacca. She recounts that a few weeks after the rape and subsequent death of Pippa, the Turkish police returned the camera with which Pippa had filmed her whole trip to her family. Looking through the footage, the family discovered that the killer had used Bacca’s camera a few days after he had murdered her to make videos of another bride: the sequences that appear are those of the wedding of a family member of the murderer. A smiling, dancing bride and joyous bridesmaids are central to the murderer’s recording. While telling this horrifying epilogue to the story, the eyes of Bianchi roll back into her head as she collapses on the stage floor.

The audience learns that at the beginning of the piece, Carolina Bianchi spiked her own drink with a date rape drug called ‘Goodnight Cinderella’. What unfolds in the next hour and a half of the play is a quasi-psychedelic trip in which

a group of actors (personal friends of Bianchi nota bene) perform a choreography with Bianchi’s lifeless, intoxicated body: a surreal depiction of the physical and mental hell one goes through when experiencing or having experienced rape. Its imagery defies the imagination, at least, my imagination; one of a male who has not been personally exposed to any form of sexual threat, let alone assault. Soundscapes of Bianchi herself are woven into this choreography, recounting once again stories of femicide. By intoxicating herself, Bianchi consciously puts herself in the tradition of Bacca and Ambramović.

During this second part of the performance, Bianchi questions whether all these stories or performances she talked about have brought any sort of relief. Has Pippa Bacca’s suffering led to anything? Was it a bodily sacrifice for a transcending, greater and global good or just a violent, sexual, local crime committed against a woman? Why can it not be both? What is there to take away from all this harm inflicted on women? What solace is to be found? How do we interpret it?

Bianchi’s answer to these questions is what really struck me. At one point Bianchi’s unconscious, semi-naked body is laid out on the hood of a car which is rolled onto the stage. Its license plate reads: ‘FUCK CATHARSIS’, telling for the way Bianchi tackles these questions.

From the second part of the performance it becomes clear that for Bianchi there is no possible solace, no relief, there is no conclusion or interpretation to be made, there is only the real, palpable pain that was inflicted on these women. The never ending testimonies of female bodily harm are neither cathartic, nor empowering, nor denigrating, nor do they bring answers or resolve, they just are. It is Bianchi’s view that whenever we try to interpret or make sense of the physical horror inflicted on women, whether during a performance or in real life (as we have seen, the boundary between the two is not always clear-cut), the trauma that lies behind it is dismissed to a degree. For example, to interpret Bacca’s

performance and its outcome either as a commendable act of feminism or as a naive act of temerity, is to dismiss the physical trauma and anger behind it. Bianchi argues that catharsis is on the side of the violator.

Bianchi resists to interpret or resolve the trauma in order to recognize the pain for what it is. What is important to her is that ‘[t]he trauma does not end at the end of the play”. [7] In its essence, the performance is a plea to postpone or resist any kind of resolvement when it comes to these stories (i.e. catharsis).

Thecla as a female body-performance

During the performance I could not stop thinking of other female bodies “at risk” closer to my own world as a student of Latin and Greek literature: Antigone, Alcestis, Iphigenia, Perpetua and Felicitas… I tried to use Bianchi’s performance and the stories told in it as a lens through which I could reread or reexamine these figures and their stories. Maybe I could approach some of these ancient narratives as body-performances in line with Bacca and Ambramović? Quickly my attention was directed to the story/performance of/by Thecla since, at least to me, it shows a lot of similarities with the stories that Bianchi recounts in her performance.

During the performance I could not stop thinking of other female bodies “at risk” closer to my own world as a student of Latin and Greek literature: Antigone, Alcestis, Iphigenia, Perpetua and Felicitas… I tried to use Bianchi’s performance and the stories told in it as a lens through which I could reread or reexamine these figures and their stories. Maybe I could approach some of these ancient narratives as body-performances in line with Bacca and Ambramović? Quickly my attention was directed to the story/performance of/by Thecla since, at least to me, it shows a lot of similarities with the stories that Bianchi recounts in her performance.

The earliest record of the story of Thecla is a 2nd-century Greek apocryphal text called Acts of Paul and Thecla. In this text, Thecla, a noble virgin woman who is supposed to marry her fiance Thamyris, disbands this engagement upon hearing the teachings of the apostle Paul. In doing so, she breaks all social conventions, choosing virginity, an ascetic lifestyle and Christianity over marriage and the community. From that point on Thecla willingly and knowingly places her body in direct jeopardy for the sake of her (spiritual) convictions. Even though she is continuously being prosecuted for her decision, she persists. First, she is condemned to be burnt alive at the stake, if it wasn’t for a godsent storm. Later she encounters a man who tries to rape her and lastly she is put through violent and public sexual assaults in an arena; stripped of her clothing and tied naked by the feet between two bulls. Just before being ripped in half, another miracle saves her from death. Thecla puts her bodily integrity on the line and is repeatedly met with sexual violence in the process. The real, bodily risk is also exactly what makes her decision to follow Paul admirable to Christian readers of the text. And although Paul puts himself through similar risks, the sexual, bodily component, the objectifying gaze is never present.

In this, you could say, body-performance avant la lettre, Thecla unveils the objectification of women, its results and the way in which it complicates the expression of her religious beliefs by putting her body at risk. But again the question is, and this is also the question that was at the center of Carolina Bianchi’s performance: what do we take away from this story (these stories) of (sexual) violence against women? What do we take away from this performance?

The trauma of Thecla: make it make sense

The modern scholarship on the Acts of Paul and Thecla is divided on the interpretation of the text and especially on the interpretation of Thecla and the physical trauma she has to endure. In the 80’s an early gender-critical approach to the text was explored which highlighted the female, disruptive elements in the text. [8] These elements were interpreted as evidence of the text’s tendency to resist the patriarchal structures at the time. Thecla was read as ‘[an] elite female heroine who defied household and city by refusing to marry and by undergoing, yet concurring physical distress and sexual aggression.’ [9] From this focus they even argued that the text must have been written by women within ‘women-centered communities’ (it originally being a folktale, an oral story told by women, for women). This interpretation tries to resolve Thecla’s trauma by identifying it as ‘female empowering’.

In more recent years however and mostly under the impulse of Rosie Andrious, a different reading has risen to the fore which disregards this female focus and alternatively lays its emphasis on the masculine rhetorics within the story; the sexual violence, objectification of Thecla and her silencing: “The ideological structure within the narrative proclaims Thecla as an object to be owned and desired (meanwhile, the only desire she is permitted is her ‘spiritualized’ desire for

Paul). In this way, Thecla is shown to be at the disposal of powerful men, and this treatment establishes hers (and woman’s) place in the world.” (Rosie Andrious – Saint Thecla: Body Politics and Masculine Rhetoric, 2020, p.123-124)

This view is radically different from the aforementioned. Andrious, highlighting the misogynistic undertones of the narrative structure, bluntly summarizes Thecla’s story as ‘[a] sadistic journey of shame and exposure [which] has given her [Thecla] the necessary credentials to carry out the orders of a male apostle.’ [10] How could Thecla’s story then, in any way, be female empowering? In Andrious’ view the anti-female terror in the story of Thecla is emblematic of the underlying patriarchal structures which not only govern the narrative, but are of paramount importance to the story. Ultimately, this interpretation too is some sort of solution: an attempt to make sense of the violence.

Resisting catharsis

Albeit very different from each other, both of these interpretations try to interpret the sexual violence, they try to resolve it. The interpretations serve as some kind of catharsis, or at least they reveal the urge of seeking one. They explain and try to make sense of the trauma. However, what if we actively try to not make sense of it and recognize it for the absurd violation it is, and only for that? Where does such a perspective take us in our experience of the story?

Central to this approach is the question of how we choose to read these sacrifices of the female body, from Thecla to Bacca? Where lies the catharsis in these stories, in these performances? When does the offering of the body stop, the pain, the lingering danger and risk? Carolina Bianchi’s performance offers an interesting new perspective. To postpone or resist a catharsis could provide a new way of reading the stories: experiencing them for the pain they entail and the pain only. ‘FUCK CATHARSIS’, at least for a moment and let us see where the pain takes us.

Endnotes

[1] Article of The Guardian on the murder of Eliza Samudio.

[2] Forte 1988, p. 218.

[3] For more on the importance of the physical body in female performance art, see ‘Bodies of Evidence: Feminist Performance Art’ by Erin Striff.

[4] The full testimony: “It began tamely. Someone turned her around. Someone thrust her arms into the air. Someone touched her somewhat intimately. The Neapolitan night began to heat up. In the third hour all her clothes were cut from her with razor blades. In the fourth hour the same blades began to explore her skin. Her throat was slashed so someone could suck her blood. Various minor sexual assaults were carried out on her body. She was so committed to the piece that she would not have resisted rape or murder. Faced with her abdication of will, with its implied collapse of human psychology, a protective group began to define itself in the audience. When a loaded gun was thrust to Marina’s head and her own

finger was being worked around the trigger, a fight broke out between the audience factions.”

[5] For Anna Mendieta’s performance see here. For more on the performance by Valie Export, see here.

[6] In feminist theory, the male gaze is the act of depicting women and the world in the visual arts and in literature from a masculine, heterosexual perspective that presents and represents women as sexual objects for the pleasure of the heterosexual male viewer. Eaton 2008, p. 873-874.

[7] Originally: “Het trauma stopt niet aan het einde van de voorstelling” – Bianchi aan De Standaard.

[8] In the 80’s no less than three monographs were written on the topic; independently reaching similar conclusions. In 1980 The Revolt of the Widows: The Social World of the Apocryphal Acts by Davies, in 1983 The Legend and the Apostle: The Battle for Paul in Story and Canon by MacDonald and in 1987 Chastity as Autonomy: Women in the Stories of Apocryphal Acts by Burrus.

[9] Matthews 2001, p.40.

[10] Andrious 2020, p.192.

Image of Pippa Bacca hitchhiking by RV through De Morgen.

Image of ‘Rhythm 0’ by Donatelli Sbarra / Courtesy of the Marina Abramović Archives.

Image of The Cadela Força Trilogy – The Bride and The Goodnight Cinderella (CAROLINA BIANCHI) by Christophe Raynaud De Lage, protected by copyright.

Icon of St. Thecla, see here.

Bibliography:

Andrious, R. (2020). Saint Thecla: Body Politics and Masculine Rhetoric. London: T&T Clark.

Antmen, A. (2010). Performing and Dying in the name of World Peace: From Metaphor to Real Life in Feminist Performance. Rupkatha Journal on Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities, 2(1), 59-64.

Burrus, V. (1987). Chastity as Autonomy: Women in the Stories of Apocryphal Acts. Lewiston, New York: Edwin Mellen Press.

Davies, S.L. (1980). The Revolt of the Widows: The Social World of the Apocryphal Acts. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press.

Davis, S. J. (2015). From Women’s Piety to Male Devotion: Gender Studies, the “Acts of Paul and Thecla”, and the Evidence of an Arabic Manuscript. The Harvard Theological Review, 108(4), 579-593.

Di Santo, G. (2022). Il Corpo di Pippa Bacca. In: Mayor de la Iglesia, E., Gorgojo Iglesias, R. & García Valdés, P. (eds.), Voces disidentes contra la misoginia. Madrid: Dykinson, 473-488.

Eaton, A.W. (2008). Feminist Philosophy of Art. Philosophy Compass, 3(5), 873-893.

Forte, J. (1988). Women’s Performance Art: Feminism and Postmodernism. Theatre Journal, 40(2), 217-235.

MacDonald, D.R. (1983). The Legend and the Apostle: The Battle for Paul in Story and Canon. Philadelphia: Westminster.

Marcheschi, E. (2019, October 5). Nel corpo, oltre il corpo: Pippa Bacca e il viaggio che continua. Arabeschi. http://www.arabeschi.it/74-nel-corpo-oltre-il-pippa-bacca-e-viaggio-che-continua-/

Matthews, S. (2001). Thinking of Thecla: Issues in Feminist Historiography. Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion, 17(2), 39-55.

Striff, E. (1997). Bodies of Evidence: Feminist Performance Art. Critical Survey, 9(1), 1-18