— written by Dr Claire Rachel Jackson, Postdoctoral Researcher in the Novel Echoes research group

What’s in a name?

Who reads novels, and why? If you ask most people this question, they’ll likely give you a strange look as if it’s a trick question. There are so many different and diverse novels in the modern world, after all, that it’s hard to imagine that there isn’t one to appeal to everyone’s taste. This has never been so true as now. During the lockdown prompted by Covid-19, sales of fiction in the UK have surged [1], and customers seem to be shunning dystopian stories for ones which can comfort, soothe, and entertain us through this unusual period. Now more than ever, novels are a fairly universal way of distracting ourselves from the current social and political situation, entertaining ourselves, and comforting ourselves with fiction.

But if you ask this question about antiquity, the answer looks quite different. The texts known in modern scholarship as ancient novels are not clearly identified in antiquity, and there is a long debate about exactly how firmly ancient readers categorised them as a single genre across their heyday in the 1st-4th century CE. The term novel is not an ancient one, and has come down to us from a seventeenth century French theorist, Pierre-Daniel Huet, whose use of the word roman for both ancient and early modern fictions has encouraged this kind of transference between ancient and modern novels [2]. Modern readers expect novels to be fictional because of our familiarity with the conventions of the genre. If ancient readers did not have a fixed concept of novels or a lot of examples to establish these conventions, would they automatically think of novelistic fiction as something natural and normal? Or would it be something more complex, something they had to confront and grapple with?

If we wanted to ask these questions about the modern world, there’d be a simple answer: ask the readers of novels and see what they say. But our evidence for who read novels and why in antiquity is extremely sketchy. The latest ancient novel dates from the 4th century CE at the latest, but the influence of the novels on hagiography, medieval romances, and early modern novels make it clear that they held significant appeal in the centuries after they were composed. Proving this, however, is a different matter. The extant testimonia to the novels in the centuries after their composition are problematic. They suggest that the novels were considered low-brow, even obscene. My personal favourite is Theodorus Priscianus, a late fourth/early fifth-century doctor who offers an unusual cure for impotence.

It is good to use readings that draw the soul towards pleasure, like those of Philip of Amphipolis or of Herodian or undoubtedly of the Syrian Iamblichus, or to others that pleasantly narrate erotic tales (Euporista 2.11.34, 133 Rose)

It’s not clear who Philip of Amphipolis or Herodian are. Ewen Bowie has ingeniously suggested it might be a corruption for Heliodorus, author of the Aithiopika (Ethiopian Stories) [3], but given how chaste this novel is by comparison to the others, it seems a bit of a stretch. But the reference to the Syrian Iamblichus suggests that Priscianus is talking about ancient novels. We know that an Iamblichus, said in one version of his authorial biography to be a Syrian, wrote a novel called the Babyloniaka (Babylonian Stories), which seems to have been quite racy. As such, this has often been interpreted as a paradigmatic example of how the ancient novels were perceived in late antiquity – essentially as a kind of low-rent pornography. But this is just one mention of one now-lost novel, not of the genre as a whole, and given the genre’s influence on religious hagiography, this cannot be the whole story. This epitomizes the paradox of the ancient novel’s reception: on the one hand, the explicit mentions of the texts are often thin, partial, and focus on just one facet of this complex genre; on the other, the subtler evidence of their influence on hagiography and later genres suggests a much more multifaceted reception. How then should we investigate the early reception history of the ancient novel?

Fallible Photius

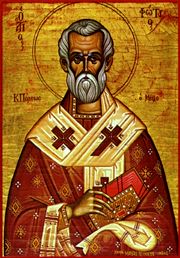

These questions form the core of my current research as part of the Novel Echoes project. My work looks at how the novels were read in their earliest reception, and how we bridge the gap between the explicit testimonia to the novels like Theodorus Priscianus and the subtler but more pervasive signs of their influence across late antiquity and Byzantium. A key figure for this research is Photius (see image 2), the ninth-century patriarch of Constantinople. Photius seems to have been a prodigious literary figure, writing letters, dictionaries, theological works, and more. But of particular interest to scholars of the ancient novel is the Bibliotheca, literally a ‘collection of books.’ The Bibliotheca is essentially Photius’ reading journal, in which he describes the 279 texts he read while separated from his brother Tarasius, the work’s addressee [4]. In this work, Photius includes a number of novels and other fictional narratives in this work, such as Heliodorus’ Aithiopika, Achilles Tatius’ Leucippe and Clitophon, the pseudo-Lucianic Ass and its likely source-material in Lucius of Patrae’s Metamorphoses. Photius even discusses lost novels such as Antonius Diogenes’ The Wonders Beyond Thule and Iamblichus’ Babyloniaka, works that would only exist in a handful of fragments each if not for Photius’ detailed descriptions of their plots [5]. Photius’ detailed summaries of a wide variety of different novels makes him a uniquely important figure in the reception history of the novel, as without Photius our knowledge of these fragmentary novels would be just barely north of nothing.

But Photius is not an infallible source. Some of the novels he describes are still extant, and by comparing the novel with Photius; version of it, we can see the differences. Heliodorus’ Aithiopika, likely written in the third or fourth century CE, is famously complicated and twisty. It starts enigmatically with two unknown figures left alive after the aftermath of a battle, and it takes roughly half of this 80,000 word novel to find out who these people are and what sparked this battle. The eleventh century Byzantine writer Michael Psellos comments on how twisty Heliodorus’ plot is, comparing it to snakes hiding their heads in their coils so you can’t see where they end or begin. Photius, however, doesn’t mention this at all. Instead, he begins the plot at the earliest chronological point of the story rather than the actual beginning of the book. This is not entirely wrong, but tells us something about Photius’ priorities that he reorders the complex plot into a chronologically linear fashion.

But Photius is not an infallible source. Some of the novels he describes are still extant, and by comparing the novel with Photius; version of it, we can see the differences. Heliodorus’ Aithiopika, likely written in the third or fourth century CE, is famously complicated and twisty. It starts enigmatically with two unknown figures left alive after the aftermath of a battle, and it takes roughly half of this 80,000 word novel to find out who these people are and what sparked this battle. The eleventh century Byzantine writer Michael Psellos comments on how twisty Heliodorus’ plot is, comparing it to snakes hiding their heads in their coils so you can’t see where they end or begin. Photius, however, doesn’t mention this at all. Instead, he begins the plot at the earliest chronological point of the story rather than the actual beginning of the book. This is not entirely wrong, but tells us something about Photius’ priorities that he reorders the complex plot into a chronologically linear fashion.

With this in mind, how should we interpret Photius’ assertion that Antonius Diogenes’ novel was likely composed near the time of Alexander? The very name Antonius Diogenes must date from the Roman empire due to its mix of Greek and Latin names, and the only mention of Alexander comes from inside the novel itself. One of the novel’s origin stories for itself is that the manuscript of the narrative was rediscovered by Alexander the Great’s soldiers. Has Photius mixed up fiction and reality? If so, how can we take any of what he says for granted?

This is one of the key questions my current research tackles. What I’m interested in is how Photius’ priorities as an editor and compiler might affect the way he discusses the novels. In other words, why did Photius compose the Bibliotheca, and what might this tell us about his interest in novelistic fiction? One possible answer comes in the prefatory letter to the Bibliotheca. This letter, which is only preserved in one manuscript and is textually pretty corrupt, is written from Photius to his brother Tarasius. In it, Photius explains that to console his brother during their absence whilst he goes on an embassy to the Assyrians, he has summarised some texts he does not think Tarasius has read before, focusing especially on the unusual and exotic (which would explain why he doesn’t mention Homer or other texts likely to be taught in schools at this time). Photius stresses that Tarasius should not expect complete accuracy from him, as everything in the Bibliotheca is the product of Photius’ memory and might well be faulty. A lot of ink has been spilled identifying exactly which diplomatic mission Photius might have been a part of, how this dates the work, and the reliability of his implicit suggestion that he and Tarasius shared reading material. But this focus on the veracity of Photius’ letter ignores the wider point, namely that Photius is clearly trying to present the work as the product of his memory and his reading tastes. Regardless of how truthful this is, Photius places a lot of emphasis on that this is his memory of the text, and thus reflects his own priorities and interests.

Fixing Fiction?

So if Photius is clear that the Bibliotheca reflects his own interests in literature and his memory of the texts, what does this tell us about his approach to the novels? Firstly, Photius’ use of language is really surprising. He does use interesting language of fiction, but not in a fixed way, as he does not use different words to describe fictional texts than non-fictional ones, or to distinguish pagan fictions from Christian ones. Most famously, he calls several of the ancient novels dramatika, deriving from the word drama, but he also uses this word to describe speeches which are theatrical and…well, dramatic. What this tells us is that Photius does not seem to have a fixed idea of fiction as something intrinsic to novels, but responds to it differently in different contexts.

Photius often describes the texts he describes in moral terms. He criticises Achilles Tatius for being obscene (not entirely unfairly), while he praises Heliodorus’ interest in chaste love. This might suggest that Photius is interested in fiction for its ethical value, where the obsessive, borderline over the top chastity of the protagonists of the Aithiopika is far superior to the cavalier, lecherous approach to sexuality of Leucippe and Clitophon. And yet, while Byzantine churchmen like Photius can have a reputation for being staid, Photius’ wide and eclectic reading tastes suggest that he was fairly adventurous in his approach to fiction. After all, while Photius criticises Achilles Tatius, he at no points tells Tarasius not to read the novel. This suggests that Photius is grappling with the same issues that often confront modern readers about whether we should read works that we feel are worthy and moral, or ones which are temptingly entertaining. Perhaps, therefore, Photius’ approach to reading isn’t so different from some of our modern assumptions about novels and fiction [6].

By looking at Photius’ approach to novels, fiction, and reading, my research considers what Photius can tell us about how some of the earliest readers of the ancient novels engaged with these texts, and how Photius’ perceptions of them as fictions can change the way we think about novels and fiction across time. It shouldn’t change your enjoyment of whatever novels you are reading though!

[1] https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/04/coronavirus-escapism-book-sales-surge-covid-19/

[2] The irony is that Huet’s work, Traité de l’origine des romans (1670), was first published appended to a novel, Marie de la Fayette’s Zayde, which demonstrates literally this crossover between ancient novel and modern romance (or ancient romance and modern novel, depending on how you prefer to think about it).

[3] Ewen Bowie (1994) ‘The Readership of Greek Novels in the Ancient World’ in J. Tatum (ed.) The Search for the Ancient Novel, Baltimore MD: 435-59.

[4] There are actually 280 entries in the Bibliotheca, but in one entry (codex 268) Photius admits he has not actually read the book he is describing.

[5] I’ve written about these novels and Photius’ role in transmitting them in two forthcoming articles: ‘The Genuine Article? Fictions of Authenticity in Antonius Diogenes’ The Wonders Beyond Thule and Photius’ Bibliotheca’ in K. Ní-Mheallaigh and C. R. Jackson (eds.) The Thulean Zone: New Frontiers in Fiction with Antonius Diogenes, CUP, and; ‘Fragmentary Fictions: Author, Text, and Reader in Iamblichus’ Babyloniaka’ in F. Middleton, T. Geue, and C. R. Jackson (eds.) Triangulationships: Between Authors, Readers, and Texts in Imperial Literature, CUP.

[6] These tensions between ‘worthy’ and ‘escapist’ fictions are visible especially in discussions of romance novels because of their subject matter, their intended audience, and perceived low-brow style.

https://lithub.com/the-unexpectedly-subversive-world-of-romance-novels/